|

The taxes you pay: Businesses feel weight of taxes at every stage By

Drew DeSilver 12/13/02

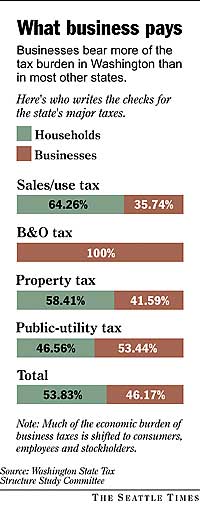

Lawmakers also will have to make some tough decisions on a passel of business-oriented tax breaks. The incentives were adopted in the mid-1990s, when Washington was flush with cash. Now, with the state looking under the sofa cushions for spare change, the breaks are sure to come under heavy pressure in the coming Legislative session. The incentives include a B&O tax credit for high-tech research and development (estimated cost in the 2003-05 budget cycle: $16.9 million); a similar break from sales tax ($61.8 million); and a sales-tax deferral aimed at attracting manufacturing, research and development to rural counties and economically depressed areas ($16.3 million). Taxing business The B&O is Washington's main tax on businesses. Most states, like the federal government, tax business profits through a corporate income tax, but income taxes generally are barred by state law. Instead, Washington taxes firms' gross receipts — their sales, in most cases — at rates that range from 0.138 for food processors to 3.3 percent for disposal of low-level radioactive waste. Seattle and three dozen other cities, all west of the Cascades, also tax gross receipts, each in their own way; 40 other cities tax businesses either by number of employees or by how much space they occupy. The B&O is a major source of funds for state and local governments. Last year, the state took in more than $2 billion from the B&O, the second-largest revenue source behind the sales tax. Seattle expects to collect more than $124 million this year from the tax, accounting for a fifth of the city's general-purpose revenue and almost a third of its parks-and-recreation fund. The B&O has one major saving grace, at least from government's perspective: It's very stable. Total collections have risen every year but one for the past decade, and only once by double digits. By contrast, corporate income-tax collections in Oregon have swung widely from year to year — down 27 percent from 1997 to 1998, up 18 percent from 1999 to 2000, and down 48 percent from 2001 to 2002. But reliance on the B&O, along with companies paying more than a third of the sales tax, means Washington businesses pay about 46 percent of all taxes — much higher than in most states. Unlike corporate income tax, which only profitable firms pay, all businesses above a certain threshold pay B&O. "Whether or not you're making a profit, you're still taxed off the top for B&O," said Scottie Marable, who with her husband owns a small manufacturers' representative firm in Bellevue. "That's hard — to pay your employees and still try to keep up with the taxes." Good for the Microsofts But if the B&O disadvantages money-losing companies, it can benefit highly profitable ones. Consider two of Washington's premier technology companies, Microsoft and Amazon.com, and how they might fare if they were subject to Oregon's corporate income tax instead of Washington's B&O. Microsoft is one of the most profitable companies in the world. The Redmond-based company doesn't break out its state and federal taxes, but for illustrative purposes let's assume all its U.S. revenue and pre-tax income is taxable locally. Had Bill Gates located his company in Oregon instead of Washington, Microsoft would owe that state's 6.6 percent corporate income tax; last year, that would have amounted to $588.7 million. Instead, the company pays Washington B&O taxes, which work out to about $313.5 million. By contrast, Seattle-based Amazon has racked up billions of dollars

in sales since it went public in 1997 but has had only one profitable

quarter. Last year, spokesman Bill Curry said, Amazon paid $4 million

in state B&O taxes. Had Jeff Bezos chosen to start the company

170 miles to the south, in Portland, the company would have paid a

$10 licensing fee. And that, experts say, points to a key reason why the Puget Sound region continues to be a new-business leader despite the tax system: The area has resources — lots of smart, skilled workers, plus plenty of lawyers, accountants, financiers and other providers of "support services" — that are hard to find elsewhere and that, especially for young businesses, outweigh any tax burden. "For most startups, taxes are way down on the list," said Jon Kuchin, a tax partner at the Seattle office of PricewaterhouseCoopers. Washington, he said, also has benefited from the presence of big engines of innovation and technical skill — Boeing, Microsoft, the University of Washington, the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center — that regularly spin off entrepreneurs and new companies. According to the U.S. Small Business Administration, the number of firms with employees in Washington grew 44.5 percent between 1990 and 2000 — the fifth-highest rate in the nation. In 2000, the most recent year for which data are available, Washington led the country both in rate of business openings and closures. The state also is a leader in attracting venture capital. According to the MoneyTree Survey, Washington has ranked among the top 10 states for both number of venture investments and total dollars invested every year since 1995. But as businesses grow, begin posting profits and start looking to expand, Kuchin said, tax issues become more important. Passing the bucks A common complaint about the B&O is that, because it applies to gross revenues, the overall tax burden gets bigger as products move through the stages of production and distribution. Businesses at each stage try to pass on as much of their B&O tax as they can to their customers, in the form of higher prices. This is easier for some firms than others, depending on industry and competition, but the more a company is able to shift its tax burden, the lower its effective tax (as opposed to what it pays directly). For the same reason, the B&O tends to favor big companies that control many stages of their own production process and disfavor firms that rely on outside suppliers and contractors. Increasingly, Revenue Department spokesman Mike Gowrylow said, Washington companies are seeking to reduce their B&O tax liability by setting up subsidiaries in other states; Nevada seems to be a favored location, he said, because it has neither a corporate income tax nor any other general business tax. Five years ago, Microsoft opened a small office in Reno out of which it runs all its licensing of software to computer makers. Last year, that licensing business was a $9 billion chunk of Microsoft's revenue, none of which is taxed at the state level. According to the Nevada Secretary of State's office, 462 Washington-based companies are currently registered to do business in Nevada; an additional 56 are considered delinquent because they haven't paid registration fees or filed lists of officers. For whatever reason, B&O tax collections in recent years have grown more slowly than the overall economy: Washington's gross state product grew by 90.5 percent between 1990 and 2000, while B&O collections rose just 71 percent. Figuring out exactly why is difficult because the schedule of B&O rates and categories has been amended several times over the past decade. Tax breaks As a rule, targeted tax incentives are severely limited by the state constitution, which bars the state from "lending its credit" to private interests and requires that tax money be used only for "public purposes." But while Washington may offer fewer incentives than, say, Oregon, there are enough that the state treasury loses hundreds of millions of dollar a year. Some benefit whole industries, such as the 1995 law that exempts

manufacturing equipment and machinery from state and local sales taxes.

The exemption saved businesses some $200 million in fiscal 2002, according

to Revenue Department estimates. Others are tailored for specific companies. The 2002 Legislature, for example, lowered B&O taxes for three years on "FAR part 145 certificated repair stations with an airframe class 4 rating and limited capabilities in instruments, radio equipment, and specialized services" — a reference to Goodrich Aviation Technical Services, which has a large jet-repair facility at Everett's Paine Field.Similarly, in 1995 lawmakers agreed to lower taxes on companies that provide "international investment management services," after Tacoma-based Frank Russell began making noises about moving some or all of its operations out of state. Frank Russell now pays B&O at the rate of 0.275 percent, 81.7 percent less than other financial-services firms. Looking for fixes Given the various issues with the B&O, it's no surprise that there have been several proposals recently to tweak the tax or replace it entirely. Gov. Gary Locke's Competitiveness Council last year recommended trying to ease the B&O burden on startup businesses, by increasing the existing small-business credit or by reducing or eliminating the tax for new high-tech companies. But the council said it would be difficult to distinguish new businesses from existing businesses that simply reorganize under a new name. Startups might gain an unfair advantage. The council also supported efforts to harmonize the 37 city B&O taxes. But as of November, only three cities — Seattle, Everett and Burien — had enacted a model B&O ordinance, and there are some key differences even in those laws. The Tax Structure Study Committee, chaired by Bill Gates Sr., last week suggested replacing the B&O with either a corporate income tax or a value-added tax, similar to those imposed in Europe and Canada. Each of those options, however, presents its own difficulties. Any income tax would have to overcome high legal and political hurdles. VATs are complicated, and since no other state has one Washington would still have a unique tax system. But Gates is adamant that the B&O has long since outlived its usefulness. "The B&O tax is anathema to me," Gates said recently. "The notion of taxing businesses that are losing money just doesn't appeal to me, and talking about whether the rate should be 0.484 or 0.275 doesn't make any sense. We should just get rid of it." From forest to furniture: Washington's business-and-occupation tax, unique in the country, essentially taxes gross sales. It brought in more than $2 billion last year, making it the state's second-biggest revenue source behind the sales tax. Cities took in $205.3 million from them in 2000. Businesses often pass along some if not all of their B&O burden to customers. Here's how that "pyramiding" process works.

|